Q&A with Germaine Sijstermans

about 'Betula'

|

"In my compositions I often strive to provide the players with a sort of biotope for the given, (rather) abstract material to occur, develop and move in an organic way." — Germaine Sijstermans

|

|

Yuko Zama (YZ): Your seven pieces in this album Betula were composed from 2017 to 2019. Can you tell me about the background of these compositions?

Germaine Sijstermans (GS): In these years I had the chance to be an artist-in-residence at Intro in Situ, a production house for new music in Maastricht (NL). In this residency I was able to better get to know myself as a composer and installation artist. I had planned to experiment with ways of working and materials, presenting them in work-in-progress presentations. All but one of the pieces on this album stem from this residency time. The conception of these seven pieces varied. For some it was as if the pitches came to me and I sought a way of handling and playing that would fit the material. One of the pieces came about during a composition mentoring week with Antoine (Beuger). Others – like the ones in works that include installation - took a longer time, being shaped by abstract forms and processes that take place in a non-verbal part of my mind. My work is neither programmatic, nor does it contain a narrative. It hands material and possibilities to the subjective perception of all that encounter it: performers, visitors and listeners. The last thing I'd want is for them to make associations based on prior knowledge. I would say that in general my biggest source of inspiration is nature and its workings.

YZ: I love your answer, "I would say that in general my biggest source of inspiration is nature and its workings." When I listened to your pieces for the first time, they reminded me of my childhood, when I would lose track of time and immerse myself in the vast landscapes of nature, the sound of trees and wind. I found it very beautiful to be able to revisit such fond memories via your music, which feel more evocative and long-lasting than listening to the actual sounds of nature via field recordings. How do you feel the connection between nature and your music (and your life)?

GS: We seem to have some similar childhood memories then! I am a big nature lover. Nature is a fantastic teacher. It's beautiful, efficient, flexible and in so many ways totally separated from our human standards and systemizations (of, for example, time). I am happy to have grown up at the edge of a forest and to live close to a forest again now. The presence of and interaction with nature in my life has been very forming and is certainly a priority in my life. Growing up I loved spending time on our balcony that was just underneath the canopy of a big birch tree, watching the swaying, long, hanging branches and enjoying the rustle of the multitude of small leaves. The view and smell of the forest beyond that was accompanied by a soundscape consisting of nature sounds (trees, birds, frogs, horses, chickens) and, most of the time, anthropogenic sounds (the busy road on the other side of the house, dirt bikes, unintelligible shouts from soccer players on a nearby field). I love visiting urban environments and metropolises, but so far I always create my works in an environment in which I am surrounded by or have a view on nature (wild or cultivated). In such circumstances I can reach my preferred state of mind of creating. In my compositions I often strive to provide the players with a sort of biotope for the given, (rather) abstract material to occur, develop and move in an organic way. What will occur will be what best fits the players and the circumstances, similar to how a natural flora is always what best fits a location. YZ: Why did you choose a clarinet for your instrument?

GS: When I was a child I followed the then usual two years of recorder lessons before choosing another instrument. At nine years old I actually wanted to play the oboe, because the timbre of it being so unlike more commonly heard instruments. I was advised to start on the clarinet and switch to the oboe later. In the end I took a liking to the clarinet and preferred it. At 10 years old I also took up piano lessons, but the clarinet always remained my main instrument. During my bachelor studies I started to play the bass clarinet as well and nowadays I play both instruments equally often in my activities as a clarinetist. I am very happy to be familiar with the physicality of multiple instruments and genres of music, because with each one you embody the sound and music in a different physical language. That is also part of the reason why I love to dance and sing for fun. I enjoy switching between these types of embodiments and I feel that on the clarinet it is possible to channel a lot (perhaps the best) of all of them into one voice. The physical and mental engagement that is necessary to do so can be very intense, but the outcome can be as well. Within that one voice the clarinet has so much to offer. It has a big range which overlaps with my own vocal range (and to an extent that of most people). I especially love its wide range and flexibility in timbre. The possibilities of extended techniques, whether subtle or in-your-face, add yet another layer to the dimensions of the instrument. YZ: I remember that you mentioned that you have worked with the same musicians of the ensemble from the very beginning until this recording of these pieces. Can you tell me more about how the collaboration with these five musicians started and then developed?

GS: For the residency and the work-in-progress presentations I wanted to work with a number of musicians that I felt comfortable with (in general and in such a process), whose playing I liked and who possessed a certain sensitivity that I was looking for. Of course, Leo and I knew each other for many years already, having studied in The Hague at the same time. There we played together a lot; newly composed repertoire in collaborations with composers, including himself, but also repertoire by Brahms, Bartók and Ustvolskaya. I had also known Antoine for a few years already, having played together mostly in the Klangraum concerts in Düsseldorf. I had briefly met and played with Rishin, Johnny and Fredrik on different occasions. As musicians I think we were a good match from the start, but through playing together regularly in such unconstrained circumstances we've become quite the ensemble. I love how we complement each other's playing, making worlds happen. I feel extremely privileged to have been able to work with this group in that process. I'll never pass on an opportunity to play with any of these great people and artists. YZ: How did you first come to know Wandelweiser composers (and/or their works)?

GS: During my bachelor studies in The Hague I would play in compositions by Leo and our friend Jeromos Kamphuis. I had heard about Wandelweiser through them and in 2013 they invited me to play their music with them and Marcus Kaiser in a concert at Marcus's house in Düsseldorf, in his Kaiserwellen concert series at the time. That is where I met Antoine for the first time. In the summer that followed I visited Klangraum for the first time and have done so almost every year since then, often also performing. I have had the pleasure of encountering many wonderful, interesting people and forms of art there over the years. YZ: What do you think were the biggest influences that you received from them? Do you think your close collaborations with Wandelweiser musicians changed your perspective on music in some way?

That first encounter was not so much an influencing moment, but rather a falling into place of things. Specifically the freedom of the 'open scores' and the space-time they help create, through a certain attentiveness, in which one contributes to the music in accordance with one's own way of being and sensory perception of the moment and environment. After that I've gone on to play many pieces, in different settings and by different composers that are (in one way or another) affiliated with Wandelweiser. I think the most important ways in which those experiences have been valuable to me are by letting me realize that this kind of experience of and acting in perception, that I had before only savored in moments of solitude, can also be experienced and shared with others (playing or not playing). From there I arrived at a point where I could put it in words and compose for others. Another important aspect of these encounters and collaborations is that they were (are) artistic environments that are free from certain cultures and conventions surrounding western classical and 'academical' contemporary music that I found disturbing and counterproductive to my intentions of making music and art. I've played my fair share of those genres in the past, mostly contemporary, and I still enjoy playing them. But I'm happy to be able to revisit those genres from an approach that lies outside certain conventions, having been formed through years of diverse activities among which collaborations with Wandelweiser artists. YZ: What kind of things did you particularly aim for during the recording of the 'Betula' album? Or what did you want to capture in the recording of your pieces?

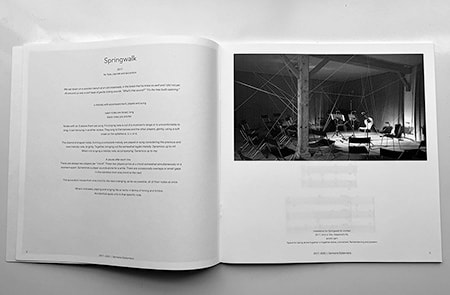

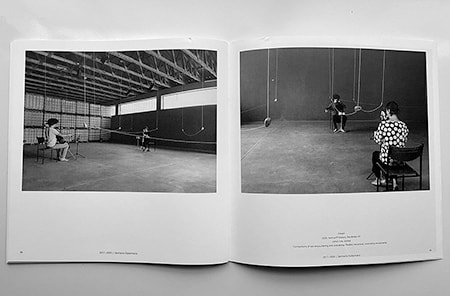

GS: During the recordings I wanted to capture the incredible ensemble playing. My colleagues on this album are fantastic musicians, each giving such wonderful realizations of the scores on an individual level and also very much so on the interactive level of the music. Playing in this ensemble, I have only experienced outcomes of the (open) scores full of attentiveness for each other's playing and the possibilities of the music. For the recordings Joel used several sets and positions of microphones, which offered a lot of options in the mixing process. We looked for a balance that corresponded to my idea of combining different aspects of the concert experience into the tracks. As I mentioned before, visitors are seated intermingled with the musicians: one will always be closer to some musician(s) than to others. So, on the one hand there will be an experience of nearness and intimacy, which includes the (often unavoidable) sounds of tone production like breathing, key clicks, bowing sounds and air flow. On the other hand, there is the experience of distance and totality, since one also hears sounds coming from further away, from within the space (and its acoustic) or outside of it. Within this interplay of nearness and distance, there are the interactions of intentional and coincidental, human and non-human (produced) sounds. When my music is played, of course I hope it will be in enabling circumstances, but I do not see the music as something that happens outside of 'daily life', requiring the players to get into a role of some sort. It will exist, as the players are, along with what exists. YZ: Your music seems to be closely connected to your installations. How do you think the nature of installations (multi-dimensionality of space, time, silence, light, etc.) affects (or becomes part of) your music?

GS: Any information we receive through any of our senses influences our perception of information received through (an)other sense(s). In that sense, the environment we experience music in always “becomes part of it”. But in another way, my installations do not become part of the music, but actually arise from the same core concept (that takes into consideration circumstances such as the architecture, the performers and their instruments, and the time of year and day). One could compare it to different fruit-bearing branches that have been grafted onto and are fed through the same rootstock. During a performance the two aspects of the work meld together again in the conscious and unconscious perception of those present. I guess that in a way I search for a type of freedom full of potential in my work, with no outcome being superior to another. My installations are transparent environments inside or parallel to the given architecture, and I specifically avoid that they become objects. The musicians and visitors usually sit intermingled in the installation. There is no one seat that offers a better sound or view than another, just a different one. Which seat someone picks is up to them. You're not forced to look and focus in a specific direction. Your focus can wander, in and out, here and there; sometimes on sounds, sometimes on the installation. Subtle changes in, for example, light can be unnoticeably slow at first, bringing in a temporal layer aside from the one experienced through sound. Perhaps these layers lure us into a pace of being in that moment, that is different from the (overly) familiar. Maybe more on par with something that was before us, or is beyond or outside of us. ( Interview conducted by Yuko Zama in May-July 2022)

|

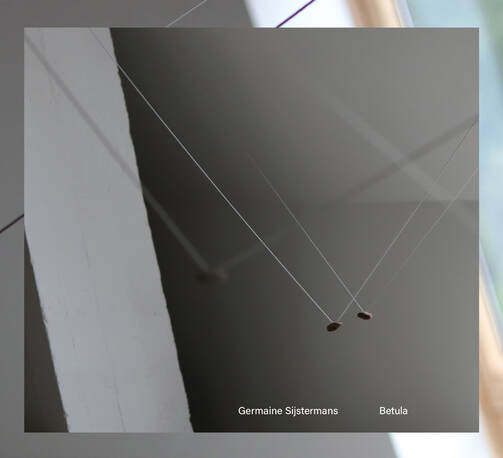

Germaine Sijstermans - Betula (elsewhere 023-2)

Germaine Sijstermans upcoming concerts/installations in the fall 2022Late August: Heim.art (*CD release concert)

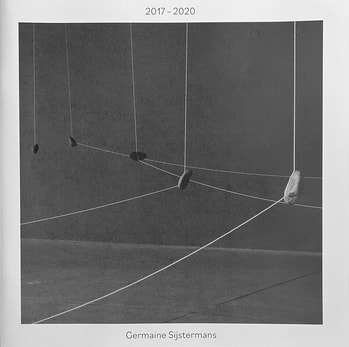

3rd of September: Cultura Nova festival (NL) (*CD release concert w/ Antoine Beuger, Leo Svirsky, Germaine Sijstermans) 21st of October: CD release concert at Intro in Situ (NL) Autumn 2022: Berlin Germaine Sijstermans - Catalogue 2017-2020 (available at Bandcamp)This catalogue contains the scores for twelve works composed by Germaine Sijstermans in the years 2017-2020, along with photographs of installations by her. The catalogue was made for the occasion of the heim.art® Lagerhaussommer 2021 concert week. Four live recordings from this concert week will be released as an EP in September 2022.

(see the details at Germaine Sijstermans website) |