Q&A with Guy Vandromme and Bruno Duplant about

‘l'infini des possibles’ (12 études pour piano)

‘l'infini des possibles’ (12 études pour piano)

|

“This co-creative process is something that many of us classically trained musicians have forgotten to develop during our scholastic education, an education that is mostly oriented on reproduction

and not on creating art work.” (Guy Vandromme) |

|

Yuko Zama (YZ): Bruno, you wrote this piece l'infini des possibles (12 études pour piano) in 2019. How did you come up with the idea of writing these 12 études? Also, can you tell me how this collaboration between you and pianist Guy Vandromme started?

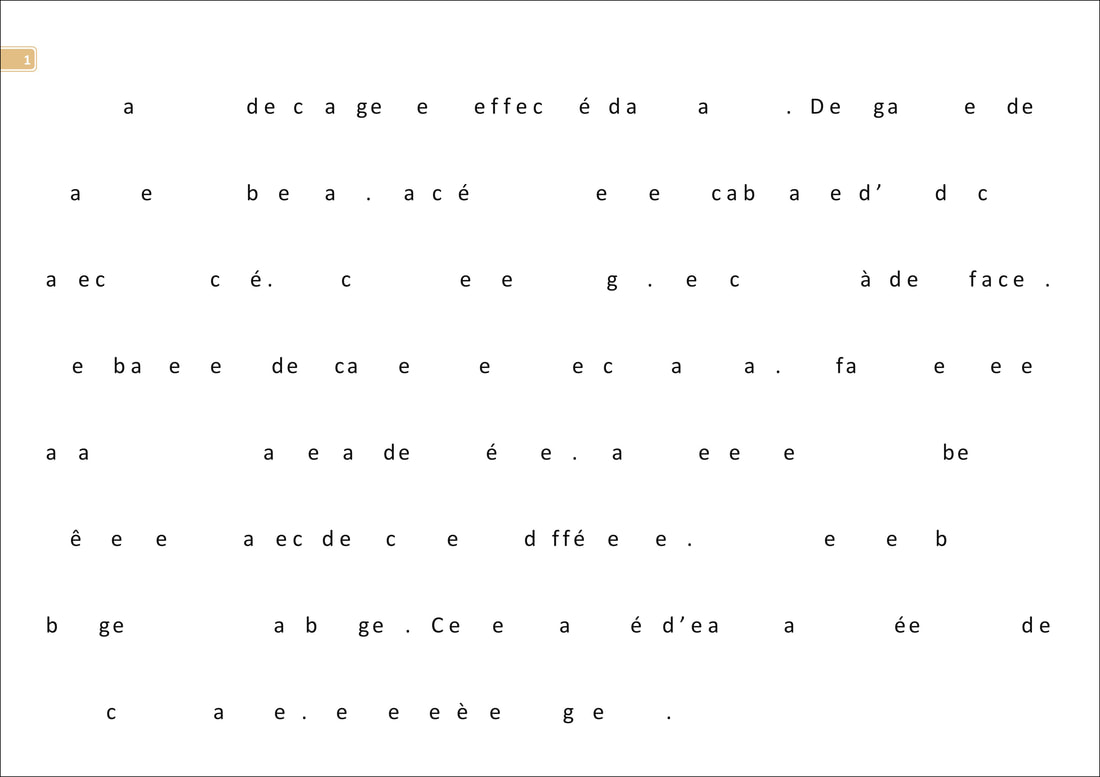

Bruno Duplant (BD): When I was listening to two recordings of Guy’s on Edition Wandelweiser (Satie's Socrate and John Cage's number pieces), I thought I discovered a fantastic pianist with a sensibility whose sound touched me deeply, as something timeless. Then, I decided to write new pieces for him. It turned out to be the 12 études for piano. YZ: Your score to this piece looks fascinating, consisting of sparsely lined lowercase letters (a, b, c, d, e, f, g) with periods and spaces in between. It was quite surprising to hear how Guy interpreted such a simple score into a delicately nuanced realization with great depth and an amazing range in this recording.

Michael Pisaro described this Guy’s realization of your score: “What begins as a black-and-white figure drawing ends as a hand-colored portrait. Those colors are beautiful: subtle, shaded, nuanced, detailed. Through the sensitive touch of Guy Vandromme the potentials of the score acquire dimension and expression.” BD: I totally agree with you and Michael’s words. Guy is a very mature, profound artist and pianist, and above all, I think he has a great sense of music. The idea of this composition was to have 12 different pieces, with 12 different colors/lights, from the brightest to the darkest. Guy and I talked very frequently on the phone in complete harmony, sharing deep understanding and sensitivity. We discussed the score, the recording material, the piano, but also as composers and pianists we looked into these studies in parallel (like Satie, Chopin, Schumann, and also Cage). Guy recorded two studies as one of his earlier interpretations, which was played in a festival in Belgium this summer. The whole 12 études on this album were eventually recorded by Guy on a fantastic, rare Steinway C from 1896 during this spring. Then, I mixed and mastered them for this album. Guy Vandromme (GV): I remember that once I received the score, the context became extremely clear. The directions were clearly set by Bruno. I also think that our intense collaboration for many months crystallized the aesthetics even stronger. The result was the 12 canvases that reflect a collaboration between Bruno and me and our artistic exchanges from the fifteen intense months. YZ: Sounds like an ideal collaboration between a composer and a performer, where both share a strong kinship and deep understanding over the entire creative process. I think this strong connection is certainly reflected in the aesthetic of this piece. Guy, what particularly fascinated you about Bruno’s score to l'infini des possible? GV: When we look at scores of Eva-Maria Houben, Michael Pisaro, Antoine Beuger, and also many composers of the younger generations of the Wandelweiser collective, we have to admit that in a very large sense of composing, these artists re-defined the language of a score. Just like it had happened during the renaissance and later also in baroque music, many aspects of indetermination again became part of the syntaxis of music. In that sense the composer creates a frame with a lot of open choices, which eventually is leading to a very high and intensive process of setting the esthetical standards of the art work together between the composer and the performer. This co-creative process is something that many of us classically trained musicians have forgotten to develop during our scholastic education, an education that is mostly oriented on reproduction and not on creating art work. All these aspects popped up also in the score l'infini des possibles of Bruno Duplant. What made our collaboration very interesting was that the co-creating process helped us each time to reshape the choices together, giving me a chance to look for how the rules of the legends would give me the freedom of interpretation and in what sense the 12 studies could be built up as the researches of 12 different color studies, where you could reduce the rhythmical and harmonic choices to the extreme to create a pure simple format on its own. These studies have nothing in common with the studies of Chopin, Liszt, Debussy, Scriabin, Cage, and Ligeti, but rather like doing research in a contemporary way to find how an idiomatic choice could help to lead the perception into 12 particular worlds on its own. YZ: Thanks, Guy, for your lucid explanation of how this collaboration with Bruno started. I like what you said, "the 12 studies could be built up as the research of 12 different color studies, where you could reduce the rhythmical and harmonic choices to the extreme to create a pure simple format on its own."

Did you have any particular art work (or any artist) or any literature (poetry, novel, etc.) in mind which could be associated with the images of a series of 12 different color studies when you composed or realized these 12 études? I would like to ask both of you the same question. GV: When I was in my early twenties, a very important conceptual American artist Martin Maloney was living in Antwerp, my hometown in Belgium. For many years he became my mentor and I had the chance almost daily to visit him in his studio to exchange ideas, while drinking liters of Italian coffee, about the history of art, the importance of Matisse, the impact of Constructivist Movement in Russia, the key essence of Mondriaan, the way George Antheil re-defined music into sound, the influence of the Muralists, the start of abstract expressionism and many other subjects. As one of the main subjects then, we often discussed the direction of the impact of the choice of the material in the art work. In reducing the choice of elements - so in bringing the concentration up to a higher level on the essence of the material - the perception would allow us to see and undergo much more the impact of the subtle changes instead of focusing on the dialect roadmap of a dialogue. I had the chance to come to the US for many weeks with my girlfriend at that time, Ilse Geens who is now my wife, to help her doing research on the work of Clifford Still, where we analyzed the importance of conservation of pigments for the monochrome artists such as Barnett Newman, Ad Reinhardt, Franz Kline, Willem De Kooning, Jackson Pollock and Clifford Still. That trip to the US, as well as the years of talking with Martin Maloney, the writings of Ad Reinhardt, the letters of Barnett Newman, Silence of John Cage, and the art review of Morton Feldman, all made it very clear that if you present a work of art, one of the first questions should always be what the material would be like. It was in the same period - the early 90's when I started to meet Antoine Beuger. I was present at the first official concert of Wandelweiser in Klangraum where Pi-hsien Chen played the sonata of Jean Barraqué and the Hammerklavier sonata of Beethoven very impressively during the same concert. Surprisingly, both works known for the uppermost complexity, were presented as one "gestalt (shape)", as a sort of "study on" a dramatic vocalisation for Barraqué and rhythmic counterpoint for Beethoven. I was so impressed that this complexity would give me the same possibility of perception as the precise condensed construction of an early work of Morton Feldman from the 50's. So, if I play a version of a study of Bruno Duplant, for me the transformation as such of the material only becomes interesting when the selection of the parameters is so reduced that one gets dragged into the choice from the start. The ideal realization of Bruno's score is that when one chooses different parameters, the whole étude would be different and become a new output of the concept. In this way, I realized many versions of the études during many months. |

|

YZ: I remember that your earlier versions of Bruno's études no. 2 and no. 5 (unreleased) were much simpler realization. It was very interesting (and also surprising) to know how your interpretation has evolved and matured later for this recording which has so much more subtleties, details, a great range, and profoundness.

Were there several versions (takes) of your recordings of each étude, and did you and Bruno pick the one you both liked best? GV: I have to admit that I never realized different recordings from the same étude. The only exception I made was that I recorded étude no. 2 and no. 5 in a hall of the deSingel nine months before the second recording I made in my own home studio. We never choose the material based upon different versions, but more focused on mastering how to make the output and the sound the most interesting. Bruno always wanted to keep a very neutral position in letting me find the artistic choices on my end. So, if I would realize today a set of 12 études again, I'm convinced that some of them would be a little alike when I would play them based on the same parameters and the same chords, but that most of them would be very different from start to the end. BD: For my part, only one take was necessary, but on the other hand we had a lot of discussions and exchanges of thoughts. Our exchanges even extended to further references, even distant ones, like John Cage, but also baroque music, the indispensable Satie, Debussy and French music of the beginning of the 20th century (in some of his interpretations), and Ligeti. Meanwhile, my literary and philosophical references are always the same, Mallarmé, Bachelard, Cage, Perec, and Ponge. YZ: Guy, I also remember that you decided to record the 12 études at your home studio, since you were not happy with the sounds of recording studios. What exactly made you decide to record the final version at your home studio (with the help of the engineer Silas Bieri for some special mic settings)? Why did the sound of your home studio feel so special to you, compared to the sounds of a regular recording studio? I think this recording has a wonderful organic feel as if the piano was 'breathing' naturally, which for me is very special. I am curious to hear your thoughts on this. GV: Looking at the history of classical musicianship the last fifty years, some major esthetic, social and cultural changes have been taken place that have an impact on our listening world today: since the ‘70s, many different musical movements have been creating their own world of acoustical environment such as the historically informed performance, contemporary electronic music, the Minimalists, the New York school, jazz, free-jazz, experimental pop and rock bands and artists and many others. What makes the classical musicianship so unique is that their existence is directly correlated with the acoustical set up of the music. Where most of the music styles do need amplification in order to exist, classical musicianship goes hand in hand with the acoustical qualities of the architectural spaces. In order to guarantee projection and exposure of the sound, classical music as per definition only exists when a natural acoustic will help to support the ‘life’ of the moving sound material. In parallel during these 50 years the recording business has set up an incredible pace of producing albums opening up all different music to the public in the living room. The new social dimension of having music available within the reach of a fingertip, where the sound environment of music is part of the world in an equalised system, is something that has today become an art in itself. Is this art of recording also a reflection of the natural acoustical identity of sound appearing in space? No. Most of the time the sound identity is recreated in the studio: here we are invited to decide what the sound looks like, we can colour the sound into whatever diaphragm we want, basically the studio engineer is able to recreate whatever sound reality you desire. Now let's go back to basics: classical music has always had this incredible bond with the acoustical environment. So, what if we would take this rule for granted and find out how we could bring this natural environment into the living room too. That is what I have been working on together with Swiss sound engineer Silas Bieri for the last two years. Convinced of the complexity of the relation between time and the multiple amplitudes classical music is generating, we found out that the selection of the hall would - as a naturally equalised system - help us to re-install the 'live' reality of recording music. So, instead of cutting up the music into equalised bits and bytes, we selected the hall and compared the reality of the music presented in a live setting with the recorded version of this natural sustained music. We were so impressed by the richness of this reality that we decided to take it even a step further: what if we only used full tracks that only tolerate cuts if the musical syntax is finished? Working on the different parts of the experiment, we came to desire to find out what would happen if we would not cut at all into this reality. All these small steps made us decide that each étude of Bruno Duplant was going to be recorded in one long take. No cuts were allowed, no equalising was used, only the time and the environment where the music took place. (Interview conducted by Yuko Zama in August - September 2021) |

|

Guy Vandromme - Bruno Duplant: l'infini des possibles (elsewhere 019-2)

*CD preorder is available on this website and Bandcamp (CD release: October 3) *Digital albums (16-bit AIFF and 24-bit HD FLAC) are also available. |