|

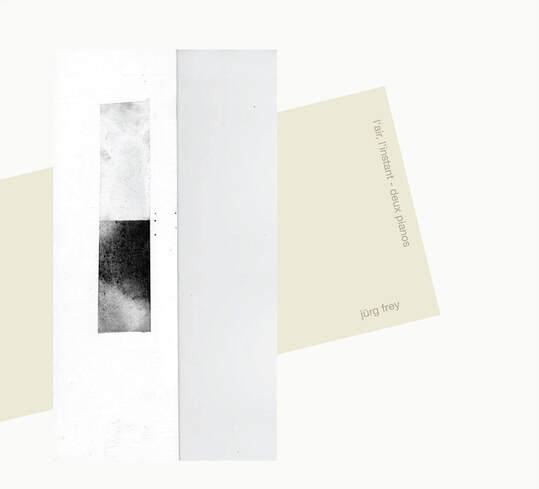

Q&A with Jürg Frey about two-piano pieces

on 'l'air, l'instant - deux pianos' “It is loose, airy, but at the same time, it is connected.”

|

|

Yuko Zama (YZ): The two pieces for two pianos, Entre les deux l'instant and toucher l’air (deux pianos) on this album, are relatively new compositions of yours, written in 2017-2019. Do you think your way of writing piano pieces has changed in some way in recent years, particularly about these two-piano pieces?

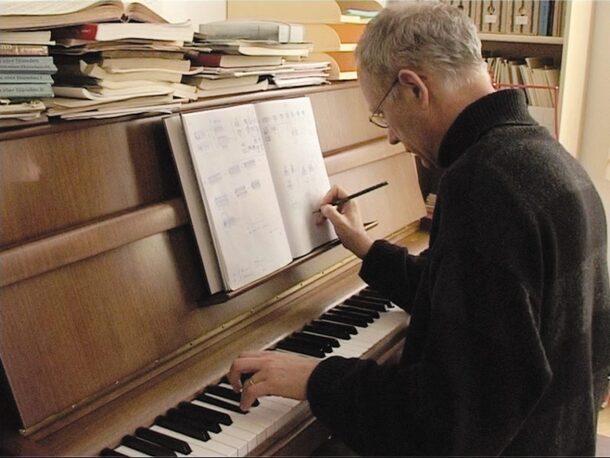

Jürg Frey (JF): I have observed changes in my writing in recent years, and this is more of a result of moving forward than having a clear plan about what to do next. I have longings, feelings, wishes for what my music could be and how a new piece could develop. The connection between the daily work on my table, my longings and the results are very complex and multidimensional. On one side, I know clearly what I do: I know the pitches, the durations, the rhythms, when and what will happen in the course of the piece, I know what they are. On the other side, I wonder: what does it mean? What kind of musical sense is coming out of this? I work on the basic material. I touch this material. I work with a vague projection of what should happen in the piece, in space, in time, but this is only a projection, I cannot give it a clear shape. I have to let it go and can only hope that it will happen as the result of my work. With regard to the pieces for two pianos, it happened to me that I found something that I have been looking for many years, but had often missed: it is loose, airy, but at the same time, it is connected. The tones are not lost in the air, they all have their light, delicate connections without obtrusiveness, I can feel my composer's hand without disturbing the music. YZ: It is interesting to see that the interaction between the two pianos in both pieces sometimes gets closer, sometimes draws apart, but they never become isolated or detached completely from each other. This fragile balance is exquisite throughout the two pieces. Reinier van Houdt, one of the two pianists on this album, said something insightful about these two-piano pieces:

"Regardless of the seemingly homogeneous sound of the two pianos, it is simply the two-ness of these pieces that opens up a space of infinitely small differences and contrasts in shades, resonances, attacks and decays, all of these coming into clear focus because of the music's unhurried pace." "To me listening to it, it's like there's two simultaneous dimensions: a hand making a drawing in infinitely thin pencil lines hovering like a mirage next to another hand painting colors without contours in beautiful deceptively monochrome shadings." (Reinier van Houdt) I think this is a beautiful description of your two-piano pieces. What was specifically in your mind when you wrote these pieces for two pianos with the idea of two-ness in contrast to your experiences of writing solo piano pieces? JF: I think in this piece, the two pianos, the two pianists, and the two parts of the score, have two different personalities. And both speak about the same or a similar topic, but feel and think in different ways. Quite often a difficulty with music for two pianos is the accurate coordination of the two parts. They have to build one body of music, and the performers have to work as a unit. Opposite to this, in my piece, I established the gap between the two as an essential element of the piece. And the interesting thing is that now a unity is created across this gap, and everything comes together in a loose way. Reinier’s remark speaks about a fact that I’ve been aware of for a long time, and it’s extremely close to my working. But for a long time, I was not sure if this dichotomy of “thin pencil lines” and “monochrome shadings” are the particularity of my music, or if it is a weakness of a composer who cannot decide for one or the other. Over the years, I began to discover and came to understand that it is something unique in my music, and I can get both together in one piece. And not just one after the other (because music is a time-based art), but all together. I can create a multidimensionality of the musical spaces, a simultaneity of different sensations that are actually mutually exclusive, but when they come together, they hopefully create a complex musical sensation.

YZ: As a listener, I can hear such multidimensionality and complexity of musical sensations as the signature of your work.

In traditional piano music, tones and chords are often closely connected with the ones before and after to create a continuing, seamless flow of music, which could evoke feelings and emotions in listeners' minds with a compelling power created from the succession of melodies and the accumulation of harmonies, like the Romantic composers' piano music does. On the other hand, there is a minimal kind of piano music that has only sparse sounds with long silences between, with each sound detached from the sounds before and after, refusing to evoke any connection between the sounds. The former has an obvious horizontal flow that gives the music a movement and a narrative context, while the latter has a vertical depth that gives the music a sense of stillness and contemplative nature. What interests me is that your piano music seems to have these both natures co-existing in a unique way, lying somewhere between flow and stillness. Each tone or chord is not tightly connected to the previous or following tone/chord to form an obvious melody, and also the two or three notes in a chord are sometimes only remotely consonant, rather connected ‘loosely’ via a long silence or openness yet without being completely detached from each other. Melodies in your piano pieces are often very vague, sometimes we hear only the implication of a melody. But when we recognize it, it evokes similar feelings and emotions as the Romantic composers' piano pieces did, but in a much subtler and calmer way. I think that this subtlety, or the thin bridge to connect the sounds to form the music via openness, is what makes your music so exceptional. Your piano music contains two fascinating natures: horizontal flow and vertical depth, a distant relation to both minimal art and Romantic music. This fascinating nature seems to be even more prominent in these two-piano pieces. The interaction between the two pianists, two notes or two chords, two movements, is so vague yet it gives the music a mixed sense of openness and closeness, coolness and warmth, separation (or aloneness) and intimacy. I think the beauty of these pieces lies here. It seems to be quiet, calm piano music with a minimal structure, but we can detect a hint of feelings vaguely in the air, a hint that could trigger a stronger image of the feelings in each listener's mind. What do you think about feelings in your music, especially in your piano pieces? JF: I’m very glad to read your descriptions of the piano music. These are observations of a very good listener and I find myself and my music resonating very well in your words. I think I should not add too much to this listener’s perspective, but I can say something from the composer’s perspective. If I start my work with the listener’s perspective, with the perspective of what kind of feelings a piece should evoke, I would be lost completely. Sure, I have feelings and longings for a certain atmosphere in a piece. But these feelings do not have timelines, it happens in a no-time area. To write a piece means to transpose it into a realm of time and space. I write notes on a paper, I play a melody, and this happens in time. That is how it works, a switch from the timeless area to the time and space reality. That sounds plausible, but it is just a pure theory, and the actual practice is quite different. I feel lucky to be a composer who can always start at the very beginning, even after many years: to write single notes, chords, pitches, instruments on a sheet of paper, and to do so before it starts to make sense. A vibration in the air happens when I write the note. This is the sensation of writing. And I try to avoid composition as long as possible. I don't want to fall into the trap of composing. I keep the horizon open and do not try to control it. Sure, I have to make decisions in the course of the composition, and I always try to make them against the background of non-composing. Many things come together naturally, and that is one of the secrets of the composition: later when the piece is completed, some of the feelings I had from the beginning come to sound through the music. |

|

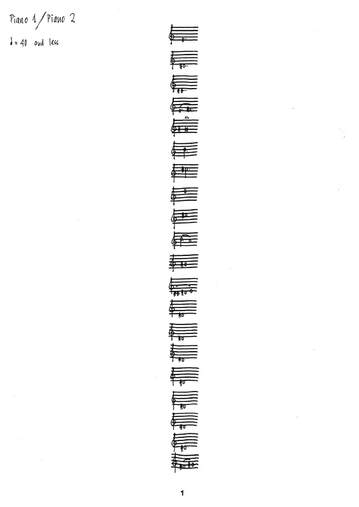

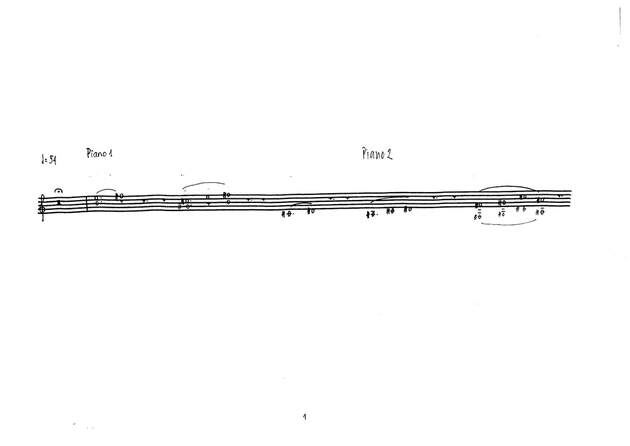

JF: To speak about toucher l’air specifically, I found myself in a rather complex territory: two independent voices, which at the same time have a relationship to each other, but which also go their own ways in slightly different tempi.

I could have written the piece in a common tempo. Then I would have converted the two different tempos into the same pulse, but with complex rhythms. In that case, the musicians would have been busy playing intricate rhythms, and the music would have sounded different. However, the score does not look like that, it looks quite easy, mostly quarter, half and whole notes and pauses, with a slightly different slow pulse for each musician. The players control the interaction by listening, following their path and pulse, it is natural music making with decisions regarding timbre, expression, rubato, not previously planned but decided exactly at the moment when they happen. This evokes the expression, the fragility and the depth that belongs to the piece. |

YZ: I like what you described as "A vibration in the air happens when I write the note. This is the sensation of writing." I can sense these vibrations from your music, especially vividly when I play your piano pieces on my piano myself. These vibrations of your music seem to be your own voice, which is different from any other composer's voice to me. There is a vague hint of feeling, or a shadow of emotion, but they are quite different from those in conventional music, much more contemporary or innovative. You seemed to have found a unique balance: being unconventional yet without completely detaching your works from feelings, often with a hint or a shadow of melodies or harmonies that we may find in more conventional music.

How do you deal with this issue in your composition, in order to make your music be your own, free from conventionalism but still containing feelings? JF: This “vibration in the air” can be also described as one step further from nothing on the sheet to something on the sheet. And it is already a strong sensation, even if it is only a single note. It is a feeling in raw and basic condition. What follows next is composition. When I say “I try to avoid composition,” it means mainly “I try to avoid a way of working that destroys this original raw state.” This is easy to say, and it is easy to understand, but it is very difficult to bring it into an art work. What we call composition technique is always quick to offer practical solutions that could take us away from this raw and basic condition. Composition technique may destroy our innermost feelings for this raw and basic material. And as a result, on the contrary, we may end up just having composition technique, whatever we may think it is, and nothing else. We know epochs in music history in which individuality played a subordinate role. I go regularly with Elisabeth, my wife (she is an early music keyboard player), to 17th century music concerts, and the music is so beautiful, even if it is very rare to recognize a personal handwriting of the composer. I hear personal decisions in details of the composition, but this is not like a search for the composer to express individuality. In this context I just had an interesting discussion with Elisabeth about this subject. We agreed that individuality played a subordinate role in the 17th century. And we asked ourselves, what is Schubert's individuality? (therefore Schubert, today we have played Schubert's String Quartets for piano four-hands). Did he write these pieces simply as the expression of his individuality? Or was it just about finding better solutions for details in the composition? Were his solutions nearer to what he felt? And is composition more difficult when feelings are complex and deep? Or would it be simply this way: Schubert found better solutions than others for what he wanted to say? I think he listened better to what he wrote and kept discovering the potential of his writing. When beauty and deep feelings happen in music, there is often something like slightly stepping out of conventionality in its background. It is like doing it in the wrong way, but not as a total wipeout or an effort to avoid conventionality, not really like turning away from conventions. And sometimes these decisions from outside the conventions could be even totally within the convention, no extra, no radicalism, with poor normality, and it sounds wonderful. Schubert again, he is a good example of just that too. It happens inevitably, and we find ourselves outside the categories. YZ: That sounds so true. It might also be the ultimate answer to the question about what gives a work of music a timeless value – just like you said, “when beauty and deep feelings happen in music, there is often something like slightly stepping out of conventionality in its background.”

I experienced some moments like this when I was listening to Webern’s Variations for piano, Op. 27 some years ago (which was a revelation to me after having listened to many of the Romantic composers' music in which a seamless horizontal flow was prominent), and also when I first listened to some of the Wandelweiser composers' works. Also, when I was listening to Scelsi’s cello piece Triphon I and II (1956) that Seth Parker Woods played at his concert a few years ago, a certain length of silence in the middle of the music struck me with unexpected profoundness – or a vertical depth. I still remember that it felt as if the old cello pieces were coming back to life in our time, staring at us vibrantly. This “vertical depth of the moment,” in which I feel the music is momentarily free from the driving force, is also the moment when I feel the music turns towards me in the middle of its flow. It is this moment when I feel the music connects with me at a deep level, away from conventionalism, or when a new unfamiliar dimension of the music opens in front of me. Such moments seem to make the music feel timeless, like when Seth played the silent stretch unexpectedly in the middle of the Scelsi piece. So, this topic might be also related to the meaning of silence, not only to momentum (or the moment when the music goes temporarily free from momentum or the flow of time). In any way, these were the moments when something about the music felt like “slightly stepping out of conventionality” as you said. Meanwhile, such a “vertical depth of the moment” could also be experienced in early music or Romantic composers' works such as the works of Monteverdi, Mozart, Schubert, and Mahler, not only in the post-Webern works. So, it could also be something to do with the performer's way of playing in addition to the composition itself. For instance, I experience such moments in Radu Lupu’s Mozart or Mitsuko Uchida’s Schubert, to name two examples from the Classical and Romantic eras. All these moments – which gave a vertical depth within the music – have become timeless in my music experience and will never fade from my memory. I completely agree with you that Schubert’s music certainly has it – a sense of “slightly stepping out of conventionality” but not totally out of conventions – which makes his music timeless. JF: You mention some examples from past eras, and it’s obvious that this question of momentum and/or the ‘vertical depth of the moment’ touches the deep fundament of composition throughout the centuries. Me too, I have my favorite examples for such experiences. The trill at the beginning of Schubert's late Sonata in B-flat Major. The holding of breath in opera, when at a fermata the whole machinery of the opera house stops for a moment. In Berlioz's The Trojans, when towards the end of the opera the music goes on and on, but in fact everything stops and does not move from its place. Composers have always had an awareness of these situations, and they have always created some ways to take the music into these realms. A significant change for me was what I learned from John Cage: that the music can not only be led there, but it can also start from there. And it can stay there for a long time, keeping contact with the silence. As long as the sounds do not become rhetorical, they can remain still and be in contact with silence. That is again such a threshold in my work, the rhetoric and the non-rhetoric of my sounds, the directions or non-directions that the sounds take, and how the sounds are put together – if the sounds keep the silences also in a context. It happens whether the transition from one sound to another is silent, or if this transition creates turbulence even when the sounds themselves are calm. This is such a delicate line between the sounds, and it is obvious that the quiet surface of my music has its origin in these kinds of sensitive questions. Here, one must sometimes put the sounds on the gold scale of meaning, but not just the sounds, also the decision how to put things together. It’s not just about being sensitive about the details. It’s also the feeling for the whole space of the composition: the weight of the material and the musical thought, the evaporation of the thought, the empty space that this creates. And then, through the work of composing, the music creates its own space. In a vocal composition by Johannes Ockeghem, there is no silence, but it is clear that around the piece there is a large, silent space, a kind of space for eternity, which is in harmony with the understanding of life of its time. All these observations from the music of the past help me to reflect these notions on my music – to understand what my music is and with what kind of responsibility I should move in these musical spaces when I compose. Space and time are not a given thing, but are created by music. Each piece of music must find its own place in the world.

YZ: One of your chamber music pieces 60 Pieces of Sound is not a piano piece but seems to have a similar sense of being “free from conventionalism but still containing feelings” that we discussed earlier.

In this piece, each of the sixty groups of sounds contains a two-part melody performed by clarinet (you) and cello (Laura Cetilia) which is half-buried under the complex sounds of the ensemble. Also, each of the sixty groups of sounds is separated via a long silence, so the connection of the tones/chords of the two-part melody is hardly recognizable. But when listening to the entire piece, the two-part melody begins to emerge vaguely and slowly like a half-transparent ghost, and it remains in the mind afterward with a faint residue of a compelling melody (which was, to my happy surprise, the extended melody of your solo piano piece Les tréfonds inexplorés des signes #32). And the more I listen to the piece, the clearer the melody grows in my mind. I think it is a very interesting piece, which presents a melody halfway and leaves the rest (to form the complete melody) in the listener’s mind, and evokes feelings via such an unconventional form. In a way, it's a unique collaboration to form the music between the composer and the listener via the performers! JF: Yes, I agree absolutely. The point is, this change in perception is not composed by me. The relation between the melody and how it is covered by the other sounds is the same during the whole piece. But your listening changes. It is similar to looking in darkness: looking changes over time. And in the composition the melody gradually emerges. And then the melody takes you by the hand and leads you through the piece, and you can say, it can happen with a piece that consists only of isolated individual sounds. YZ: This relation between the actual sounds and what we may form in our mind (as a listener) is interesting. It’s like hearing the music somewhere between reality and contemplation, overlapping both externally and internally, by filling the gap between the sounds to form the music in our mind. In a way, it could be a more active way of listening to the music.

What do you think about such active listening involving the listener’s mind/imagination in contrast to passive listening? JF: The distinction between active and passive listening is complex and not easy to describe. Would it be not listening at all if we do nothing and just wait? The activity of a listener is sitting silently and doing nothing. Music begins and I hear and I am touched by the sounds, melodies, pauses. But this is not an activity, it just happens to me. But then, my mind and my body start to interact with the sounds. I may hear connections, my memories start to work. I may create forms of the piece in imagination because I remember details of the passing piece. This way, I may have an inkling of what might come. It is a multidimensional listening: the accurate time when the sound appears, the past, the future, and all my thoughts and feelings in different directions. I sometimes compare the listener's situation to a membrane that captures the sounds and begins to vibrate. And it resonates in the listener, in his mind, his soul, his body and his intellect. This membrane could differ depending on the music. Sometimes it could be a piece of strong materials, sometimes – and I think it may apply to my music – it could be a delicate hint of nearly nothing. But even in the two piano pieces, it is different: With toucher l’air, this membrane could catch colours, vague sounds, and hints of energies with a tendency to be airy. Entre les deux l’instant takes almost nothing to suggest these moments of in-between and the membrane is so thin that it is almost permeable to the sounds. We may actively start considering that something has happened, after listening to the music when our brain begins to work with language and we may look for the words to describe the ineffable. I'm not minimizing that at all. I like to read thoughts about music, I like the discussions. It is a complement to the situation of listening, where everyone is alone with their feelings and thoughts. YZ: “Membrane” seems to be a perfect word to compare the act of listening. Listeners should have open minds to receive what is happening to them while hearing the music. Also, I could probably rephrase the words “active listening” to “reacting to the openness of the music.” In this regard, I have another question about the openness in your music from a different angle – from the perspectives of the performers who play your music. For example, R. Andrew Lee seemed to crystallize the minimal aspect of your piano pieces (on his 2012 CD of ‘Piano Music’ and 2014 CD of ‘Pianist, Alone’) by highlighting the independency of the tones/chords, detaching the cozy relation between the tones/chords that could normally create a narrative flow of a single united music. He kept the reactions between the tones/chords to the minimum, and it gave the piece a unique vertical depth. This independence and a clear separation of the sounds evoked in me the minimal artworks of Donald Judd. On the other hand, Philip Thomas played your piano pieces – like on Pianist, alone (2) on his 2015 CD of ‘Circles and Landscapes’ – very differently. He played your pieces like Feldman's pieces, with a flow in which the tones/chords were naturally related to each other. His style seemed to emphasize the horizontal narrative flow of your pieces rather than the individuality of each tone/chord. It was very interesting to compare both recordings, since it proved that your piano pieces could have quite different impressions depending on how the pianist plays – vertically or horizontally. When you compose a piano piece, do you consider giving such openness for the interpreter (pianist) to play in their own ways? Or, do you have a particular realization (including tempo) in your mind which feels ideal for your piece to be performed? JF: I don’t think I consciously consider giving such openness when writing a piece. It just happens, it’s part of my work and my life. I try to make a piece as clear as possible, and then the piece passes into the care of the players. I consider it a positive quality of my music that it could sound different under different interpreters, and that is part of the communication between composer and player. I remember the making of the first recording with Andy Lee. In fact, I didn't have contact with Andy before and during the recording process. I knew he would record the pieces, because he had asked me for that, and later, one day I just had the CD in my mailbox. I loved the clarity of his piano playing and the beauty of the sounds. But I was also irritated. I didn’t think about such an interpretation: the verticality of his playing, which largely avoided horizontal melodicism. And it took me some time to really understand it. And then I learned this: he plays exactly what I wrote, just the sounds. He brought out a trait in my music that is quite central to me, but which had never been heard with such clarity. It was a deep experience, a profound lesson in composition, notation, performance, and I am always grateful to him for this insight into my music. With regard to Philip's recording, I was already more prepared for what an interpretation of my music can trigger and that there are different perspectives. I knew Philip already and had worked with him previously. I see this as a great privilege when my music is played by such good pianists. They give their musicality, their craft, their sensitivity and their insights to my music. And even when I know what I do when I write music, these players help me more and more to understand what that is.

YZ: I remember your 2015 interview with Brian Olewnick about ‘Grizzana and other pieces 2009-2014’ on the Another Timbre site. It is a great interview, and I was particularly fascinated with the link between your music and the works of Giorgio Morandi. Morandi's painting of still life objects seems to echo with your music in a similar way; they can be seen as abstract images although they are actually figurative paintings. The nature of his painting is minimal yet it has a hint of warmth and a sense of organic life.

Your two-piano pieces on this album reminded me of this connection again, in a sense that your music overlaps with both the realm of abstract minimalism and the realm of romanticism. The sounds of two pianos are only remotely connected, often heard as individual sounds detached from each other rather than a part of a flow of the melody, but the melody emerges gradually and discreetly as we listen to the sounds. I love this vagueness and a distant sense of togetherness melding to form a melody. It is a mixed sensation of ambiguity and clarity – or clarity filtered through ambiguity – just like the still life objects and landscapes that Morandi’s painting slowly emerges to our eyes. When you composed these two-piano pieces, did you feel any connection with Morandi’s paintings? JF: I am happy to say, in relation to Morandi, I am like a devoted amateur: I love his painting. Without thinking too long about it, they give me a strong sense of presence and life. Regarding my compositions, Morandi is more of a voice in the back room. And usually when I work on a piece, I forget about this back room. As I said before, even when I know what I do, it’s not easy to understand what it is. With Morandi I found the possibility to think of my music as both: abstraction and figuration simultaneously. Abstraction as just the sound, space, time. Melody as a statement, a figure, a message. I think an important part of expressions and feelings regarding my music is about this threshold – this balance between abstraction and figuration and, to take care of them so both can remain alive at the same time. YZ: Interesting, since it seems to echo with how you composed Entre les deux l'instant, the second piece on this album. In this piece, the two pianists played two different parts, Melody and List of Sounds, alternately.

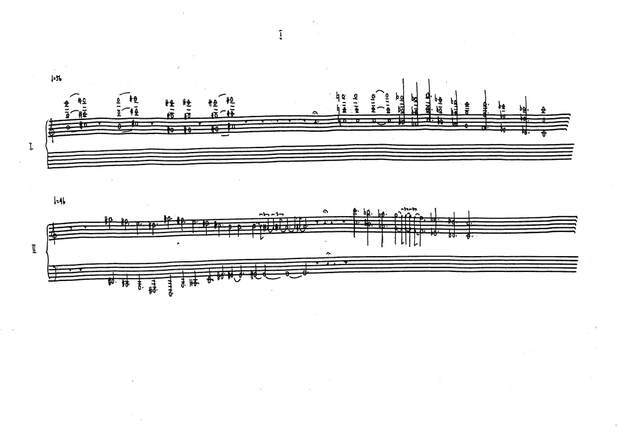

It has a fascinating structure, as if the note(s) or chord(s) from the List (which both pianists played in different timings) were casting lights and shadows onto the simple horizontal line of the Melody. It also reminds me of what you said about “abstraction and figuration.” The whole piece contains a unity within a flow of music without falling apart, keeping a careful balance between the sounds of the two pianos. The attention that the two pianists – Dante Boon and Reinier van Houdt – paid to each part and also to the entire piece are virtuosic and impressive. Also, one of the most beautiful aspects of this piece is the air (space) between two notes (or chords) or between two pianists’ sounds, which sometimes get closer or fall away or meet at the same point, like two planets floating with a distance between but always connected to each other via a thin, invisible thread. What did you intend to attain when you decided on this structure (consisting of Melody and List of Sounds)? JF: In fact, there are two pieces in Entre les deux l'instant: one is the melody, played alternately by the two pianists, and the other is the list of sounds (the same for the two pianists) to be played from top to bottom in an individual tempo of each pianist. Again, we encounter the gap here. The gap between the two pianists, and also the gap between the two pieces. I think this gap brings gentle energy and subtle flow into the piece. The music does not sound complex, but in the underground of the composition is a complex conceptuality. It is an energy inside the composition and it has a subtle influence on the surface of the piece, in the sense that I do not have to touch many details on the surface, but can just let them happen.

YZ: Another piece on this album, toucher l’air, was composed after Entre les deux l'instant. When you composed toucher l’air, did you have any connection between the two pieces in your mind?

Also, in toucher l’air, the tones (chords) of the two pianos seem to be connected more closely to form a more recognizable melody than in Entre les deux l'instant. Did you have a different concept in mind when you newly composed toucher l’air? JF: I try to remember how it started with toucher l’air: A couple of months earlier I finished another piece toucher l’air, written for the clarinetist Carol Robinson, and she played it on Birbyne, a clarinet-like instrument that is still played today, mainly in Lithuania. It is a collection of 12 short pieces. I took some of that material, added new material and spread it in time and space and built this airy, vague flowing architecture. When I wrote the piece for Birdyne, I had never thought about writing the other piece for two pianos. I normally consider the idea of trying something new and different in a similar style and/or in relation to another piece as a limitation. And when such thoughts arose, I scared them away. It doesn't mean that there have to be many obvious and subliminal connections between the two pieces. But this came to my awareness later, when I started to think about the pieces: I saw how the idea of two and gap had developed differently in the two pieces, toucher l’air and Entre les deux l'instant, sometimes even in opposite directions. YZ: In the scores of both two-piano pieces on this album, there are clear notations for the scale and duration of each note/chord, but it was not strictly instructed on how and when the two pianists’ parts interact with each other’s sounds, so each pianist could play their own part with their own decision. It seems very challenging for pianists since their sensitivities, their keen attention to the other pianist’s sounds as well as what is going on with the entire flow of the music, are all crucial to determine how these pieces would sound.

With this openness of the score, if these pieces are performed by two different pianists in the future, do you think the resulting music would be very different from these? JF: On the surface of the piece, it will be slightly different when the music is played by other pianists. This is due to the nature of the score, not part of a freedom for musicians. The scores require each pianist’s decision at each moment of playing for many details, and differences will happen. But we have to distinguish this from some kind of sponginess or arbitrariness of interpretation. When I write a piece, I want to be as precise as possible, I want to anchor precision and clarity in the composition. It's something like the roots of the composition, a strength underneath when the music is airy, spatial, floating. It doesn't refer to the tones and the way of playing on the surface, but to the inside of the composition. It doesn't refer to construction and how things are put together. Precision is a conceptual core, the strong base for what happens on the surface. And as long as the sounding on the surface remains connected to this core, it will always be this piece, even if it may sound different each time.

YZ: On the first page of your score to Entre les deux l'instant, you quoted a fascinating poem of Georges Haldas as below:

Ce n’est pas lui Ce n’est pas elle Entre les deux le vent la musique Et la vie Et la mort Et le temps Entre les deux l’instant (*English translation) It is not him It is not her Between the two the wind music and life And death And time Between the two the moment (Georges Haldas, 1917 -2010) YZ: This poem seems to perfectly echo with Entre les deux l'instant. The concept of in-between has always been my strong interest, too. There are people and other living things and objects in this world, but what actually makes things interesting is not the objects or people themselves, but the invisible threads between them, or the way they interact with each other, or the thoughts and imaginations formed in the relationships between them. When I was listening to your two-piano pieces on this album, I thought about this notion of in-between. It seems that you composed these pieces by focusing on what would be occurring in between the sounds of the two pianists, or in between two sounds or chords, or in between movements. It evoked in me some minimal art in a way that emphasizes the empty space in the air between objects, where our imagination can flow freely to form our own supplemental images with our subjective minds/reactions. What do you think about this notion of in-between, or "two" and "gap" in your words, in regard to your compositions (especially piano pieces)? JF: That’s right, one of my first deep and conscious experiences of the between emotion comes from minimal art, when I encountered Carl Andre’s sculptures and Agnes Martin’s paintings. And I tried to evoke a similar sensation with some of my earlier pieces in the 1990s, especially with my WEN cycle, a collection of solo pieces: a few sounds, much time, the presence of space. I still consider this cycle as something like the alphabet of my musical language. Since then, the idea that there is empty time and empty compositional space runs through many of my pieces. And as soon as there are several musicians, this idea of between becomes a musical space that opens up between the players. Normally, in the interplay between musicians, this is called coordination. But too often this is a nailed down box, albeit a flexible one. When I take care of this between, I do so with the awareness that this between is not something for me to take care of. I take care of the notes, in a way that it results in a kind of between. It's this untouchable space that you cannot enter. It is the void that allows my music to breathe. And I know sometimes I go very far, so that the voids are almost everything, and the music is disappearing. The emotions appear gently in this delicate, subtle world, and I let it happen. When I encountered the poem of Georges Haldas the piece was already finished, but didn’t have a title. The poem begins with two lines that say what is not, not him, not her. It opens an emptiness. Then comes a list of what's in between: wind, music, death, time, moment. All things that you cannot touch. As a material, it goes to the limit of nothing, but in our feelings and in our emotions, it is very present. And for the music it says, you can indeed touch the piano, the keys, but the composition always makes you aware, there is this space, wind, music, death, time, moment. The essence of these terms is, they are untouchable.  Jürg Frey (photo ©Alannagh Brennan) Jürg Frey (photo ©Alannagh Brennan)

YZ: I am glad that I asked this question since you gave clear words to the notion of between in your works, which was always in my mind but was hard to describe myself.

I would like to ask a few more questions about toucher l’air. This piece is divided into seven parts via long silences in between. The other day, I played each pianist’s part of toucher l’air in a faster tempo on my piano with no long silence between the parts. In this way, the whole piece seemed to form a melody more obviously in a continuous flow, similar to normal piano music. Meanwhile, when it is performed in a rather slow tempo with long silences in between (as in this recording), it feels as if the music were slowly assimilating with the air of the room, the rhythms of my breathing, the movement of my mind, creating an intimacy between the music and me. This slow tempo gives such a contemplative depth to the piece, compared to the same piece performed in a much faster tempo. It is interesting to see how tempo and the length of the silences between the seven parts affects the depth of the listening experience of the same piece. What do you think about the relationship between tempos and compositions? JF: When I look back at the past 20 years in my work, I keep seeing pieces that have no tempo at all. Just material and standstill, but over the years I have approached topics that actually belong essentially to composing as well: pulse, melody, rhythm. And even if the music feels static sometimes, there are still tempos, a variability of slow tempos. But it's actually simple: the more clearly the music has a tempo, then the more clearly it has a direction, the energy running throughout the piece from beginning to end. And a direction of the energy is always narrowing the wide, open time. I’m working to keep a balance between directed energy and openness of time and space. This sublime situation, to keep it open and to give a direction simultaneously, is still an object of my sensitivity and inspiration. Density, looseness, tempo, and flow, are working together. I have also written some pieces that are almost fast for the way I walk, for example in Circular Music. It may sound “similar to normal music” as you said. I just watch how the wide space changes. The music takes the listener by the hand and leads them through the piece. It’s a clear line. In contrast, the center of the two-piano pieces is to take the listener by the hand, but to leave the way gently open. YZ: Why did you compose toucher l’air as seven individual movements which connect to each other via long pauses, instead of one long continuous piece? JF: The seven pieces are in a similar mood, but hanging in the air as individual pieces. In a certain sense, the pieces do not speak to each other. The material in each piece is such that they are single individuals. They need enough air around them. I had the impression: if I bring all seven pieces together as one architectural form, it would make it too heavy. The piece would then not be flexible enough to be associated with the matter of air. But the idea of a continuous flow is of course not far away and had an influence on the work. The pieces are usually 2-3 minutes long, with the exception of No 5 and No 7, each of which consists of two or three materials combined into one piece. It happened that way, but it was exceptional and was not intended originally. So, it's not just a collection of seven individual pieces, there's also the idea of flow and connection. And the idea that the cycle has a direction leading up to the last and longest piece. I remember, I was really thrilled when I discovered the possibility to go with the piece into this multidimensionality of the form. The individualities of the pieces and the architecture as a whole go together. This is also my idea that a form is always related to emotions. (From the dialogue exchanged between Jürg Frey and Yuko Zama via emails during December 2020 - February 2021)

*Still images were taken from Tim Parkinson's video interview on YouTube. |

|

Jürg Frey - l'air, l'instant - deux pianos (elsewhere 014) is available on CD as well as digital album (16-bit AIFF and 24-bit HD FLAC). Also available on Bandcamp.

|