- Bruno Duplant

- >

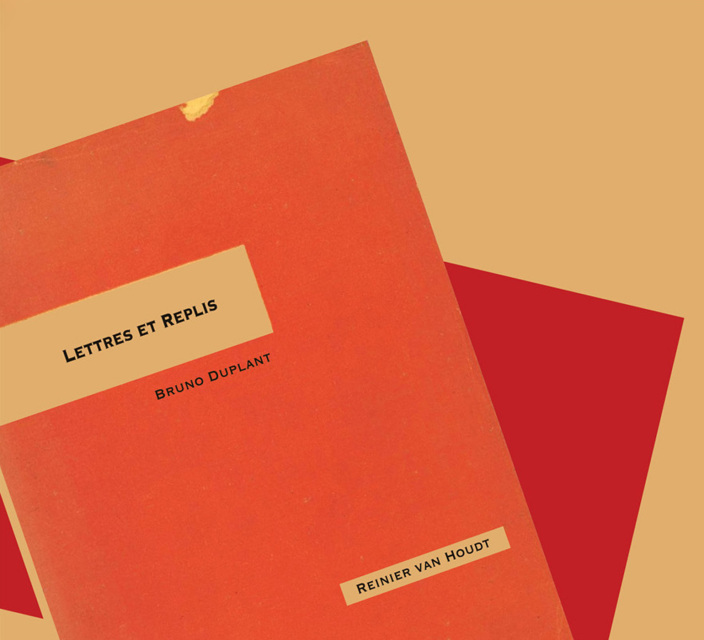

- Reinier van Houdt - Bruno Duplant - Lettres et Replis (Lossless)

Reinier van Houdt - Bruno Duplant - Lettres et Replis (Lossless)

SKU:

$10.00

$10.00

Unavailable

per item

Lossless Digital AIFF (16bit/44k)

elsewhere 008

This album contains six pieces written by French composer/artist Bruno Duplant, all composed and realized by Dutch pianist/composer Reinier van Houdt. Cover design by Yuko Zama.

For CD format, go to this page.

For digital HD FLAC (24/96), go to this page.

|

TRACK LIST

1. Lettre 1 11:02 2. Replis 1 9:44 3. Lettre 2 8:31 4. Replis 2 8:08 5. Lettre 3 8:00 6. Replis 3 12:47 (released June 22, 2019) CREDITS

Lettres et Replis (2017-2018) scores by Bruno Duplant composed and realized by Reinier van Houdt piano recorded by Kees van de Wiel at Willem Twee Studios in Den Bosch on January 22, 2019 and Reinier van Houdt in Rotterdam on August 8, 2018 field recordings by Reinier van Houdt made on John Cage's 100th birthday on September 5, 2012 along the Maas Harbour in Rotterdam mixed by Reinier van Houdt mastered by Bruno Duplant design by Yuko Zama produced by Yuko Zama p+c 2019 elsewhere music |

Bruno Duplant's scores 'Lettres (pour Reinier van Houdt)' (2017) are three letter-form scores personally addressed to van Houdt containing letter sequences distributed across the page. 'Trois replis d'incertitude' (2018) are also three letter-form scores but with the notion of 'repli' (meaning 'fold' in a Deleuzian postmodern baroque sense as well as 'withdrawal' of incertitude and reactionaries toward the neglect of ecology, humanism, and culture). Duplant's scores also reflect Mallarmé's notion of textual space and chance, leaving a large room for the interpreter/performer.

Van Houdt’s realization of these scores are like his ‘reading’ and ‘replying to' Duplant’s scores, with composing three ‘Lettre’ pieces with multi-layered recordings of his piano sounds, and three ‘Repli’ pieces with his piano recordings and his field recordings. Van Houdt’s delicately nuanced piano sound, translucent overtones and rich resonances increase nostalgic colors and melancholic shadows as the record develops. “I composed my realizations around the fundamentals of reading and writing. The Lettres are connected to melody spelled out and read in all directions propulsed by memory and gaze. The Replis are connected to the harmonies from a place as they permeate and unravel through the metaphorical holes made by writing, linearly arranged again with recordings of a walk along the river that traverses this place. Letters cannot be erased, they affirm the materiality of language. Words (like music) are not envelopes containing clear messages, nor are they loaded guns as Sartre would have it. The possibility of meaning is rooted in the dark side of language where destruction and meaninglessness precede all possible worlds.” (Reinier van Houdt). REVIEWS

John Eyles, All About Jazz The joint credit for Lettres et Replis is fully justified by its music. The six tracks—three "Lettres" and three "Replis" ("repli" translates as "fold," not "reply")—are performances of letter-form scores by France's Bruno Duplant, personally addressed to Dutch pianist-composer Reinier van Houdt, containing letter sequences distributed across the page. As so often, listeners do not get any glimpse of the scores themselves, so are in no position to judge the realisations on the disc. But Duplant's scores are not prescriptive, and left a lot of interpretation open to van Houdt as the performer. The three "Lettre" tracks are effectively van Houdt's replies to Duplant's scores, in which he multi-layered his piano sounds. In "Lettre 1," he makes extensive use of the extremities of the piano keyboard, which would have been physically difficult, if not impossible, without multi-layering; the piece soon becomes a dialogue between the high and low ends, with some movement away from the extremes but no rapprochement between the two. Houdt allows plenty of space for the music to breath and notes to resonate, imbuing the piece with an impressive sense of drama. Although significantly different, "Lettre II" shares many of that track's strengths including its sense of space and drama; with many of the notes sounding damped, at times it gives the impression of prepared piano. "Lettre III" is different again, but is unmistakably of the same family, the three hanging together beautifully as a threesome. The three "Replis" pieces are sufficiently different from the "Lettres" to be distinguishable but, like them, work together as a group. On each of them, van Houdt combined his piano recordings with field recordings he made on John Cage's 100th birthday, September 5, 2012, along the Maas Harbour in Rotterdam, a combination which works well and produces some distinctively memorable passages. As with the "Lettres," these three have a consistent sound and style, largely down to those field recordings, which colour each of them. "Replis III," at nearly thirteen minutes the album's longest track and its closer, typifies the three and merits special mention; opening with the sounds of an outdoor field recording, it soon adds deep rich bottom-end piano which creates an atmosphere that persists throughout the piece, one that will conjure up different emotions for different listeners, all of them dark, melancholy and persistent. All in all, a haunting piece that brings this excellent album to a fittingly fine conclusion. Peter Margasak, Bandcamp Daily A gorgeously meditative yet vividly-present project — a kind of musical correspondence — Lettres et Replis was conceived and initiated by French sound artist and composer Bruno Duplant. In lieu of standard-issue scores, Duplant sent personal letters to the record’s featured musicians (including the revered Japanese guitarist Taku Sugimoto); all but the notes in the musical scale (A B C D E F G) were removed from these letters, leaving plenty of gaps of varying spaces. Apart from an instruction to play softly, with a sense of nostalgia, seriousness, and suspension, it was left to the performers to decide how to interpret them—duration, attack, and chordal choices. The Dutch pianist Reiner van Houdt created multi-layered readings of the letter scores, playing in a recording studio as well as his home. His three renderings are marked by a sublime touch, a Satie-esque delicateness—tracing elliptical, ruminative melodies of remarkable tenderness, rich in overtones and ambient noise. Van Houdt advanced the project further by creating three corresponding reply pieces drawn from the same library of piano recordings edited and layered with field recordings he made along the harbor in Rotterdam on John Cage’s 100th birthday on September 5, 2012, exquisitely and subtly pushing his responses to the letter scores toward an exterior space, as lapping water, distantly passing boats, and muffled fauna gently commingle with patiently decaying notes. (9/3/2019) Michele Palozzo, Esoteros One must always keep an eye on the margins of the musical avant-garde, where some of the most difficult challenges of contemporary production are still undertaken without clamor, with a devotion equal or superior to the “great classics”, by authors as well as performers. In today’s art of the piano, figures such as Reinier van Houdt and R. Andrew Lee have distinguished themselves for their strenuous commitment alongside the post-minimalists and the Wandelweiser collective – the “composers of quiet”, as Alex Ross put it. The prolific French author Bruno Duplant is not part of the latter circle, despite having collaborated with several artists related to it. In fact, over the course of a decade he has become a recurring element of the most radical improvisational research, an experimental fringe that intends musical creation as a constant dialogue with silence (or the illusion of the same). Following the omnipresent spirit and the controlled alea of the enlightened John Cage, over time the new musical composition has left more and more space to the interpreter, in many cases making him an actual co-author of the pieces, no longer intended as rigid schemes but rather as meager instruction manuals aimed at triggering the performer’s sensitivity and sonic inventiveness. Thus was born the remote dialogue between Duplant and the aforementioned Van Houdt, placed at the two ends of an “hermetic” correspondence expressed in sequences of letters scattered on a sheet, a blank map of a creative process yet to be imagined. In the three “Lettres” the textual characters are translated on the piano into isolated “phonemes”, tonal microcells which in the (probably randomized) juxtaposition made in the studio by Van Houdt become the details of a richly decorated melodic plot, with anomalous details derived from the preparation of the strings. From the first to the third letter the unfolding becomes gradually more enigmatic, as if it were intended to evade meaning more and more resolutely. The “Trois replis d’incertitude”, on the other hand, are not intended as answers to the relative missives, but rather as “folds”, as theorized by the philosopher Gilles Deleuze (which in turn took up the baroque thoughts of Leibniz): reality as a stratified plane crossed by space-time diagonals, “intersections, inflections through which philosophy, the history of philosophy, history, sciences, the arts come into communication” [*]. Compared to the anti-narrative nature of the twin pieces, the replis have the appearance of dramatic nocturnal meditations of vaguely romantic memory, also arranged in the order of an ideal descent into darkness – in this case perceptual rather than semantic – interspersed with field recordings carried out along the port of Rotterdam on the day of the Cagean centenary (September 5th, 2012). Conceptual art is often thought of as something rigorous and detached that has little or nothing to do with the emotional sphere. It was therefore a happy occasion when Bruno Duplant’s authorial “surrender” and Reinier van Houdt’s profound sensitivity were able to (not) meet and give life to a sonic and spiritual harmony that belongs unequivocally to both. (1/2/2020) Bill Meyer, Dusted Magazine Do not let yourself be tricked by the homophones. Lettres et Replis does not translate as Letters and Replies, but Letters and Folds. Still, let’s let the monolingual English reader’s likely first association lurk on the page, because this album is all about the unpredictable consequences of putting words out there. This music originates with ideas set to paper, but they’re not your usual notes and staves. Composer Bruno Duplant’s approach to composition could not be more personal. He writes a musician a letter, and the musician plays the letter. For Chamber and Field Works 2015-17, Duplant the invitation that he sent to Taku Sugimoto doubled as the score. This time he sent three pages of text to Dutch pianist Reinier van Houdt, who used what he found on them to fashion three “Letters” and three “Folds.” Each letter is a layered realization of prescribed notes, played quietly and layered as van Houdt saw fit in a recording studio. The layering enabled him to insert precisely selected preparations (notes modified by an object on the strings), and also to juxtapose note combinations that otherwise could only be played by a musician with the arm span of a gibbon. But while the combinations are many and unusual, the yield music that is not dense; you could fly through its spaces like a bird. Van Houdt saves all his heaviness for the foot that rests on the sustain pedal, which makes certain bass notes roll on and on, and otherwise plays with gentle consideration. Fold, as the word is applied here, is not a bend in the page, although the use of that word ensures that you will think of one. Van Houdt explains the concept in a text on the record’s Bandcamp page: “Trois replis d'incertitude’ (2018) are also three letter-form scores but with the notion of ‘repli’ (meaning ‘fold’ in a Deleuzian postmodern baroque sense as well as ‘withdrawal’ of incertitude and reactionaries toward the neglect of ecology, humanism, and culture.” The folds seem to be reactions comprising thoughts and feelings that are influenced by an awareness of what is happening and not happening in one’s time; in other words, knowing everything we know about what people willingly ignore in this era of accelerated change and destruction, we fold like poker players who have run out of chips and just don’t want to know what’s being dealt in the next hand. Such dark thoughts certainly correspond to the brooding, ruminative quality of each “Replis,” and if a listener ponders the concept of the word while listening, such thoughts, it can’t help but influence their experience of the music. In addition to piano, van Houdt layers field recordings that he made on John Cage’s 100th birthday (September 5, 2012). Knowing their origin will further provoke the listener to think of this music as being with a certain lineage, one they might already be thinking about given the sculpting influence of preparations upon certain piano notes. And knowing that these sounds sat in storage for six years before van Houdt applied them to this music may help one to think about the temporal space that can be contained within a “Replis.” Phrases from the “Lettres” reappear in each “Replis,” creating a feeling of connectedness that holds its sprawl music together and gives each play through the feeling of inhabiting a bounded zone of sound and time. There’s wordless poetry in the distance, both temporal and pitch-wise, between the notes, and a rich blend of familiarity and not-knowing in the hints of traffic and nature that course through each “Replis.” While there’s a lot to be gained by pondering the ripples of influence and event that Duplant initiated when he wrote his letters, the sound of this music is so gorgeous that it holds up just fine without any meta-awareness. (9/26/2019) |